For Beethoven, Prometheus was an idealized mythical figure with whose adversities he could identify: as he became painfully aware of his impending deafness, he could draw strength from the story of the Titan who stoically endured an unjust punishment for having brought gifts to mankind (life-giving fire, and in Viganò’s scenario, music and all the arts as well). But he did not “heroicize” Prometheus—who was already a Titan, after all. If one analyzes the ballet, there is nothing beyond the opening music that was given as a solo to the dancer in the role of Prometheus. Instead, it is Prometheus together with the star dancers—Signora Casentini, in the role of the woman, and Viganò himself, as the man—who dance at the culmination of the work, where the “Prometheus-melody” repeatedly makes its appearance.

There is thus nothing in the finale music, or in the choreography one would expect from Viganò, to allow one to conclude that this melody was exclusively identified with just Prometheus. Rather, in a finale where both gods and humankind are celebrating, the music represents the summit of human achievement—whereby man and woman have earned, through their avid development with the help of Prometheus and the other gods, the right to consort with them, to jubilate with them, and—let it be said—to greet them as equals (other than for the slight problem of mortality). But the pains of mortality are forgotten in the jubilant music of the finale. Melpomene’s dance is left far behind, without an echo to suggest its continued presence.

It is just in this context that one has to appreciate the significance of the “Prometheus-melody” for Beethoven: it encapsulated for him the progress mankind could make with the help of the arts, particularly when he found that its bass could be treated separately, then built up A due, A tre and A quattro, and so provide a miniature of the humans’ tentative steps on the way to mastery. In short, by calling it a “Prometheus-melody”, we must take the name Prometheus to refer not to the god himself, but to the story of the whole ballet, which resonated fully with Beethoven’s philosophy.

This is not to downplay the significance of the Prometheus myth for Beethoven personally. Given that he wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament while he was finishing the op. 35 piano variations, the importance of his identification with an unjustly-punished gift-giver in helping him through his crisis of confidence cannot be understated. But by the time that Beethoven had completed opus 35, and began immediately to work on the plan for an E-Flat Major symphony in which this melody would play a culminating role, the music itself had come to mean much more for Beethoven than just an expression of his relationship to, or identification with, the myth. It symbolized for him the full import and purpose of his mission as composer: to express in glorious sound the degree to which man could aspire to Olympian heights through music — his music, Beethoven’s music. And since only he could bring this work to full fruition, the music itself became the golden thread which pulled him through his labyrinth of despair (“Hope creat[ing] / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”169). It brought him to new powers of expression, and strengthened his confidence in wielding them—witness the wholly unprecedented form, and the unbounded energy, of the Eroica finale, to say nothing of the Eroica as a whole. The glory of Beethoven’s Prometheus-music is that, through its use at four different times in this crucial stage of his career, it allows us literally to hear, as in no other sequence of works, and by the use of a single theme, the breakthrough which Beethoven made from the classical to the romantic world.

The Eroica and Napoleon. Having set this context for the Eroica, we now ask: Where does Napoleon fit in? There have been many attempts to synthesize Napoleon with Prometheus; the scholarly urge to do so is irresistible, and is given impetus by the connection, through Viganò, with Vincenzo Monti’s epic poem Il Prometeo, dedicated by its author to Bonaparte. I shall not add to them.

To me, the case needs no such connection, or synthesis: it is abundantly clear that, having just finished a major new work, and thinking he wanted to move permanently to France, Beethoven was trying to use the only economic power that he had to bring about such a move, by dangling the prospect that he would dedicate it to a person of such importance.170 It also must have been intellectually satisfying to Beethoven to regard Napoleon (for a time, at least) as a present-day embodiment of the Promethean ideal. Perhaps it was in this sense that he wrote “geschrieben auf Bonaparte” (“composed on Bonaparte”) across the title page of the Eroica. (He could just as accurately have written “geschrieben auf Prometheus”, but only he would have understood the reference, while everyone could relate to Napoleon. And, so long as one is angling for maximum economic benefit from a new score, it does not hurt to flatter the powerful dedicatee even more—what does it matter if there is that funeral march to explain?)

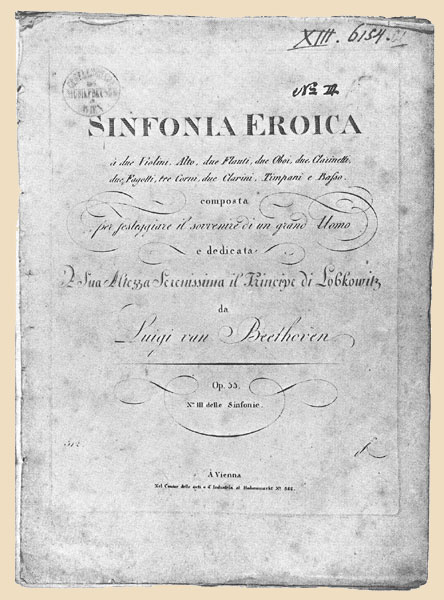

It is also clear that when Napoleon thwarted Beethoven’s hopes of a move to Paris, by literally crowning himself Emperor, Beethoven reacted in the only way his republican soul allowed: first in anger, by scratching out the dedication (actually, more than a dedication—an “entitling” [“intitolata”]), and then in irony and satire, by inscribing on the title page that the symphony was “composed to honor the memory of a great man”. (Emphasis supplied by the present author; the irony is Beethoven’s.)

There yet remained indelible the stamp of Prometheus on the Symphony; no mortal’s failings could rob it of its integrity. Such an observation suggests why, perhaps, despite his falling out with Napoleon, the Symphony remained Beethoven’s favorite for the rest of his life.171 At a time of increasing despair and anguish over his impending deafness, Beethoven rallied his creative forces around the figure of a Titan who refused to surrender to an unjustly imposed punishment. His work on the ballet Prometheus, and the theme which arose from that work, became the vehicles by which the composer brought himself to a new threshold of creativity, which was to be of deepest significance musically for himself and for the nineteenth century.

ENDNOTES

169 Shelley, Prometheus Unbound, act iv, quoted supra, text at n. 63

170 Notice that this scheme could work only in connection with his planned move to Paris. Once Beethoven decided to stay in Vienna, he could no more publicly dedicate a major work to an enemy of the state than he could have composed a set of variations on La Marseillaise. The proof is in what actually happened: the dedication in 1806 went instead to Prince Lobkowitz, an acknowledged patriot who raised at his own expense troops to fight Napoleon’s armies (see Plate I).

171 Thus according to an anecdote related by the poet Christoph Kuffner (TDR IV, 29; Thayer-Forbes, 674).